72

S

tate

of

I

ndia

’

s

L

ivelihoods

R

eport

2015

return on investment (ROI) appears better.

However, many farmers do not keep a

detailed account of costs and benefits arising

out of dairy farming. Theymention that such

calculations are a proof of the unviable prices

that they get and will force them to consider

winding down the business. One trendwhich

is clear is that the younger generation of

farmers is not keen to continue this business.

Ashok More, a small farmer in Pune taluka

who had a few indigenous cows since the

1970s, commenced cross-breeding of his

animals when it was introduced in the

mid-seventies. He benefitted from the

increased milk production of cross-bred

cows at 10 litres a day and hence increased

his herd size gradually. In the early 1990s,

he had as many as 15 cross-bred cows.

However, during 1993–95, there was a

business downturn since the local coopera-

tive was not able to procure all the milk

due to glut in production in Maharashtra.

Since milk marketing became an issue, he

decided to decrease the herd size. When in

2000s, milk was again in demand and he

wanted to increase the herd size, his sons

did calculations of income and expendi-

ture of the dairy business and refused to

join saying, “it was not profitable.” At

present, he has only five animals and he

and his wife carry out dairy farming. He

engages one labourer for milking. He sells

raw milk locally at

`

26 per litre and meets

the demand for pure milk from consumers

who want to buy from him directly instead

of buying packaged milk. At this price,

according to him, he is not making any

profit. However, he is using dung for farm

manure and cow urine is collected and

sold to a trader for Ayurvedic preparations.

If the value of these is calculated, then

profitability improves. He feels that unless

farmer gets a minimum of

`

30 for cow’s

milk, the dairy business is not profitable.

Incomes from dairy farming are a sig-

nificant source in smallholder farms. At the

lowest class of landholdings, incomes from

livestock form almost 25 per cent of total

revenues (Table 4.7). Across all farmhouse-

holds, income from livestock formed about

12 per cent of the total income. Viability

of dairy farming is critical to most farm

households and critically so for small farms.

The question of cost and incomes from

animal farming was addressed by the NSSO

in its 70th round national survey. The survey

results indicate that there is a cash surplus

when income and expenditure is compared

in all the major states (Table 4.8). The non-

cash expenditure in the form of own labour

and captive sources of feed and fodder are

perhaps not part of the reckoning. Dairy

farmers in some states such as AP, Haryana,

Gujarat, Orissa and Tamil Nadu seem to

produce higher surpluses per rupee spent

compared to other states.

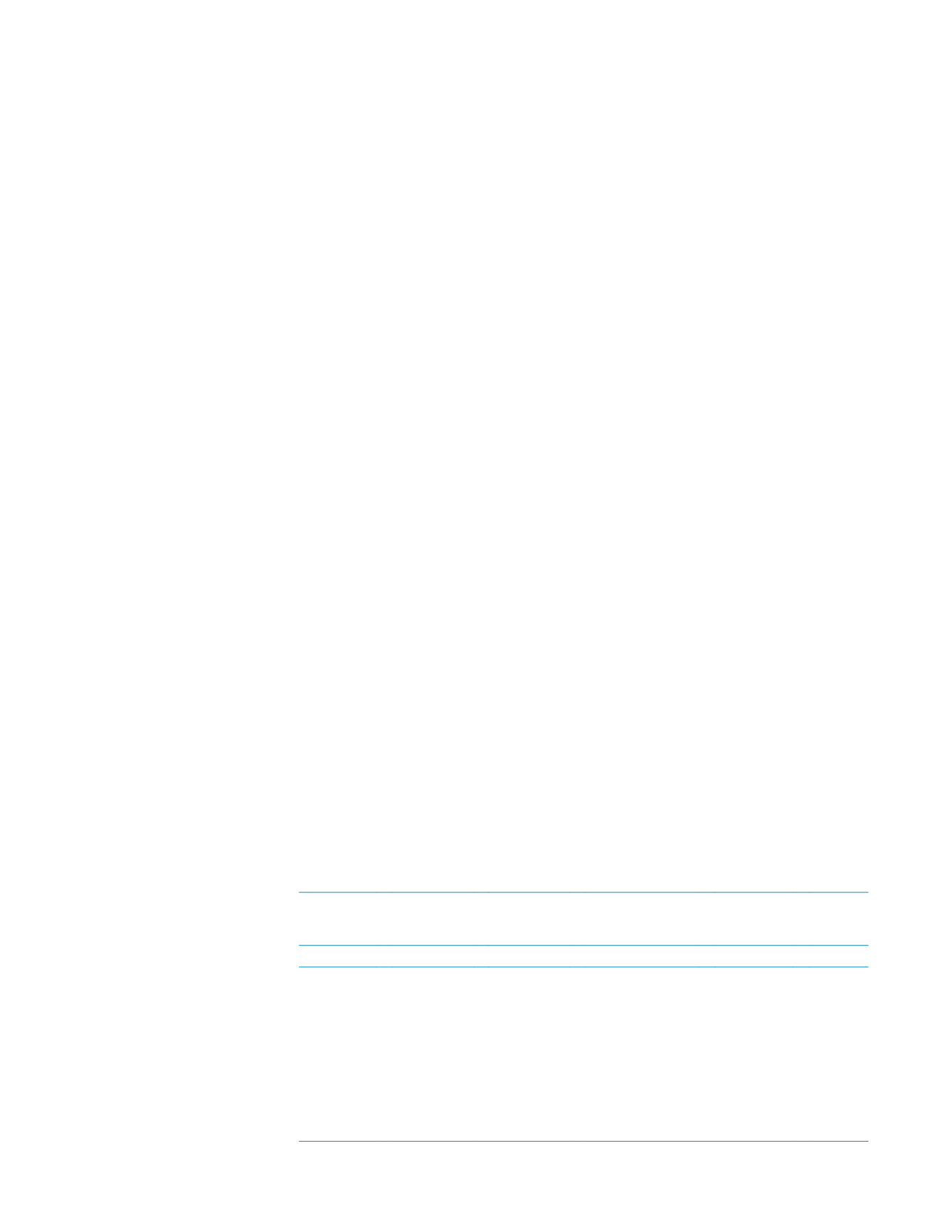

Table 4.7:

Average monthly income of farm households from different sources 2012–13

Size class of

land possessed

(ha)

Income from

wages/salary (

`

)

Net receipt

from

cultivation (

`

)

Net receipt from

farming of animals (

`

)

Net receipt

from non-farm

business (

`

)

Total

income (

`

)

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

< 0.01

2,902

30

1,181

447

4,561

0.01–0.40

2,386

687

621

459

4,152

0.41–1.00

2,011

2,145

629

462

5,247

1.01–2.00

1,728

4,209

818

593

7,348

2.01–4.00

1,657

7,359

1,161

554

10,730

4.01–10.00

2,031

15,243

1,501

861

19,637

10.00 +

1,311

35,685

2,622

1,770

41,388

All sizes

2,071

3,081

763

512

6,426

Source:

Key Indicators of Land and LivestockHoldings in India, NSSO70th round, December 2014, NSSO, MOSPI; GoI.