i nc lu s i ve f i nanc e

5

and business use, reinvestment of money in business and

keeping track of business income and expenditures as

being critical for strengthening financial capabilities of

entrepreneurial women.

Finally, apart from banks, financial inclusion can be

brought about by alternative agencies such as financial

co-operatives of the poor, based upon informal agencies

and channels such as SHGs, primarily of women, wherein

the decision-making power and profits are retained in the

hands of the members themselves. Indeed a strong lobby

for financial intermediation by federations of the poor

continues to challenge the orthodox view of banks that is

generally shy of lending to such community organizations

or even to involve them in a significant way as agents in

their banking operations.

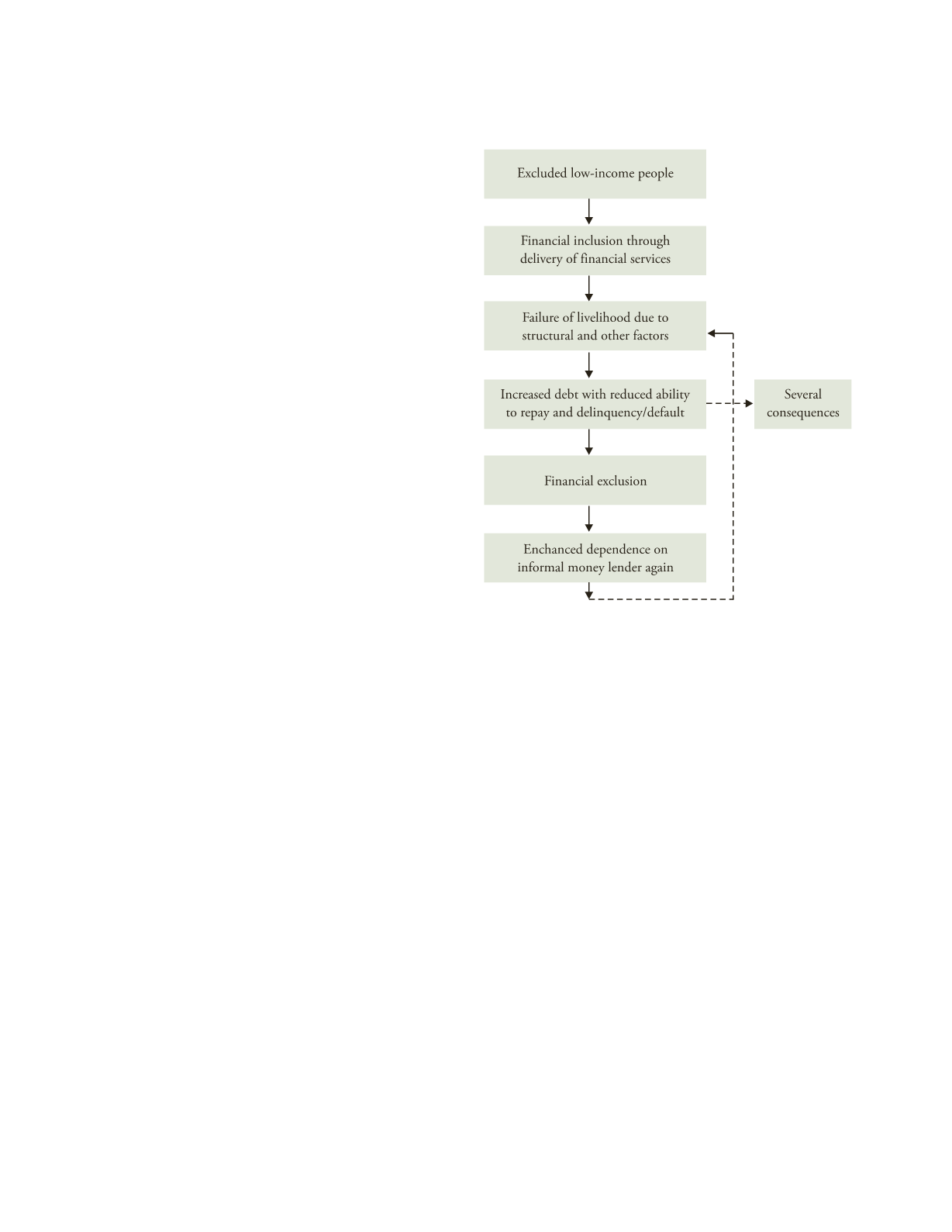

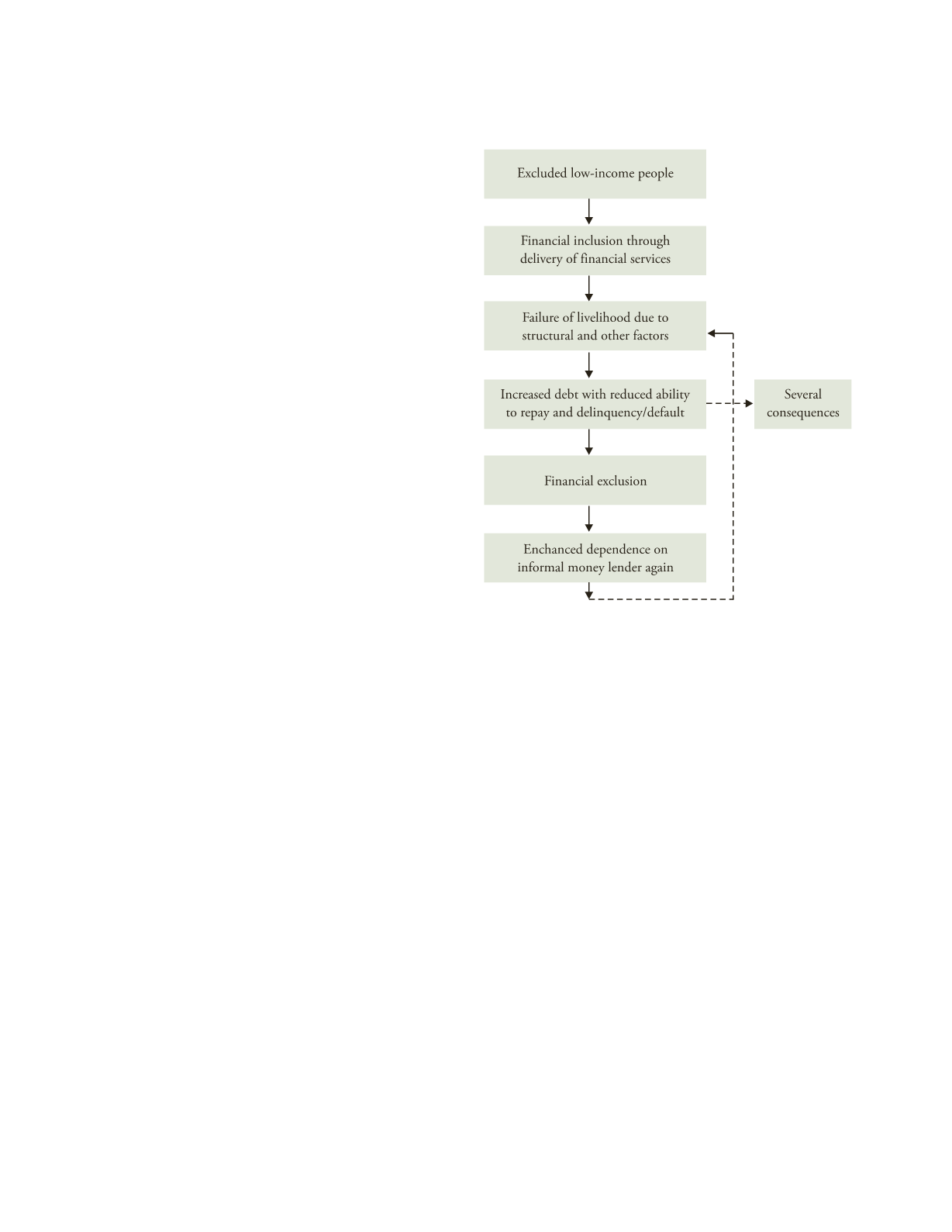

1.3 AN ALTERNATIVE PARADIGM

Before discussing the extent of financial inclusion and

aspects of the financial inclusion discourse in India it may

be instructive to look more closely at the link between

financial inclusion and poverty. Once the link between

the larger poverty phenomenon and financial exclusion

is recognized there is a case for a more substantive and

broad-based agenda of development of which finan-

cial inclusion can only be a part. Arunachalam (2008)

poses the question

whether financial inclusion can help

reverse the current paradigm of inequitable development,

and if so, how is to be operationalized?

He asserts that to

truly financially include the poor requires consistent and

simultaneous mechanisms for the management of a

variety of risks and vulnerabilities, otherwise, people

who have been temporarily included would be excluded

again, and be forced into a

cycle of inclusion and exclusion

as shown in Figure 1.1.

15

Financial inclusion without

addressing structural causes that result in the failure of

livelihoods is bound to fail, and can thus not be restricted

merely to opening savings accounts and providing con-

sumption credit.

Arunachalam argues that a new paradigm of financial

inclusion is required, which reduces risk and vulner-

ability in the livelihoods of the poor, (i) resulting from

imperfect markets (ii) helps to create strong safety nets

for the poor (iii) enables the poor to pursue diversified

and migratory livelihoods and create risk-management

mechanisms and products, such as post-harvest loans and

warehouse receipts for small holders, to ensure that they

stay financially included. This necessitates that the finan-

cial inclusion paradigm becomes the integral part of an

overall livelihoods framework protecting and promoting

livelihoods. Similar to the financial capability approach,

this too involves a larger and longer vision rooted in the

economic security of the poor rather than the current

concerns of financial inclusion.

1.4 EXTENT OF FINANCIAL EXCLUSION IN

INDIA: AVAILABLE ESTIMATES

Several estimates have been made in recent years of the

extent of financial access and inclusion. The major ones

are presented in this section.

(i) The All India Debt and Investment Survey 2002

(as quoted in Christabell and Vimal Raj, 2012)

estimated that 111.5 million households had no

access to formal credit. It also showed that the lower

F

IGURE

1.1

Cycle of Inclusion and Exclusion

Source

: Arunachalam (2008).